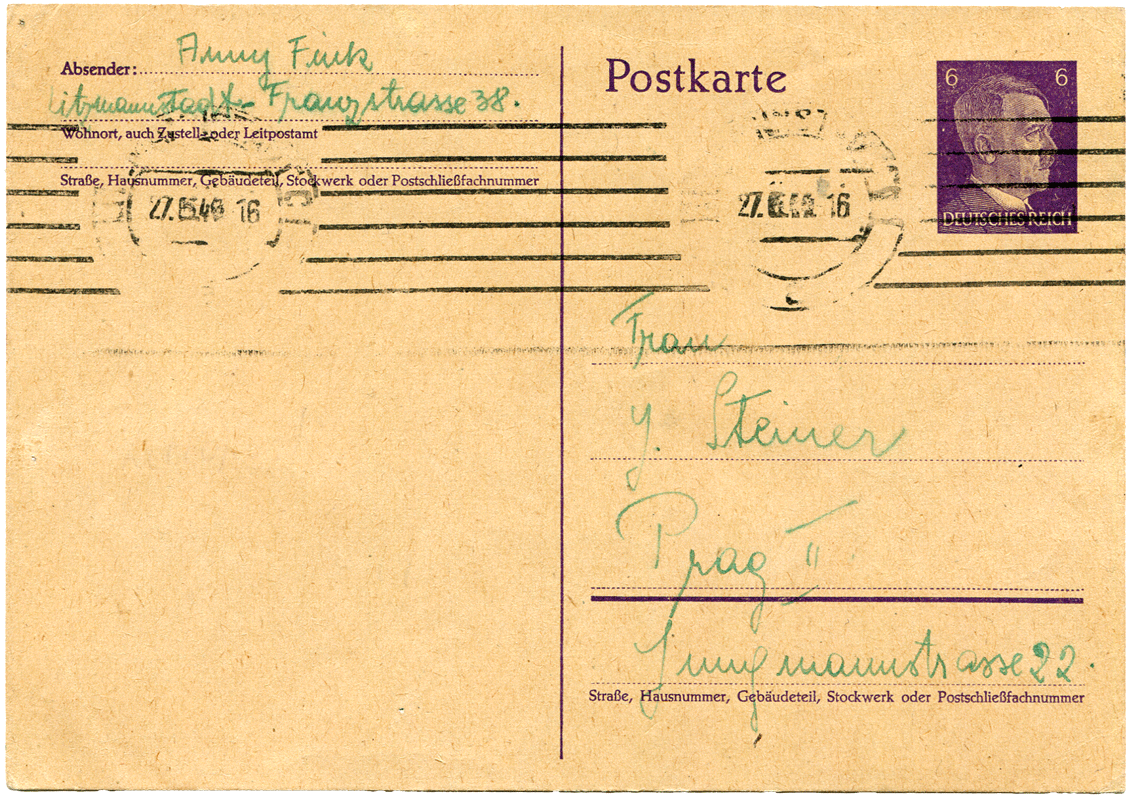

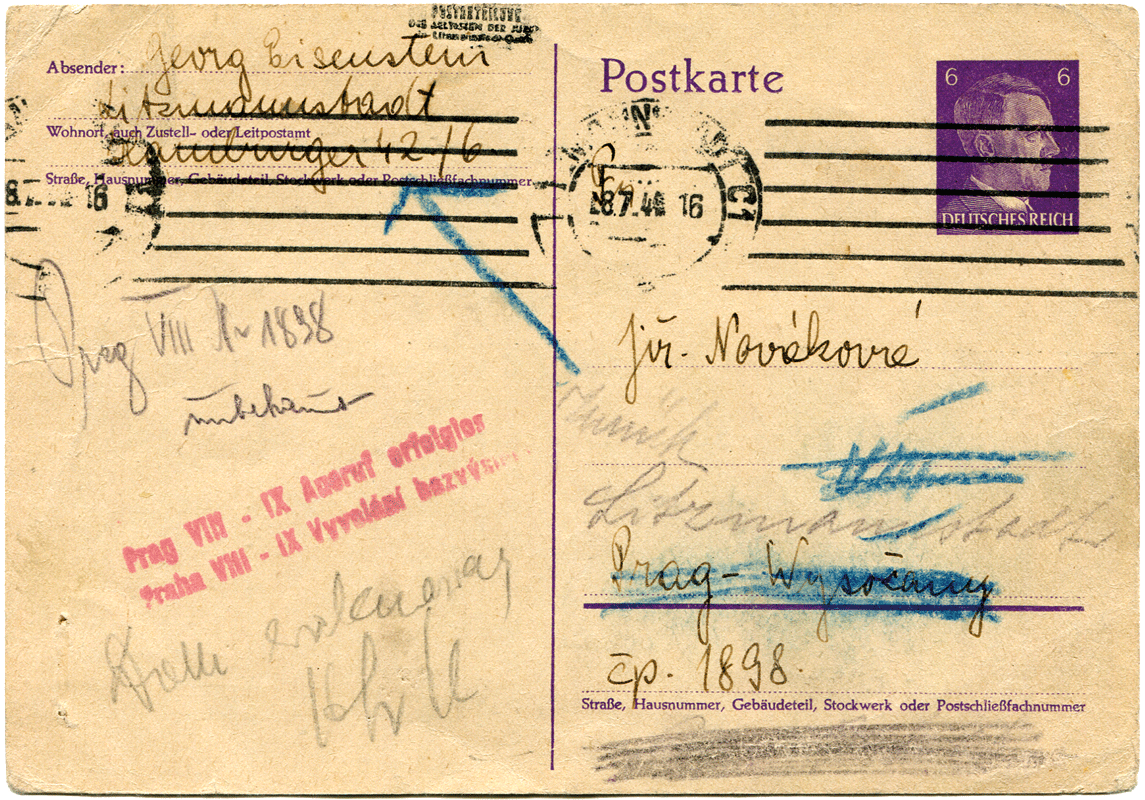

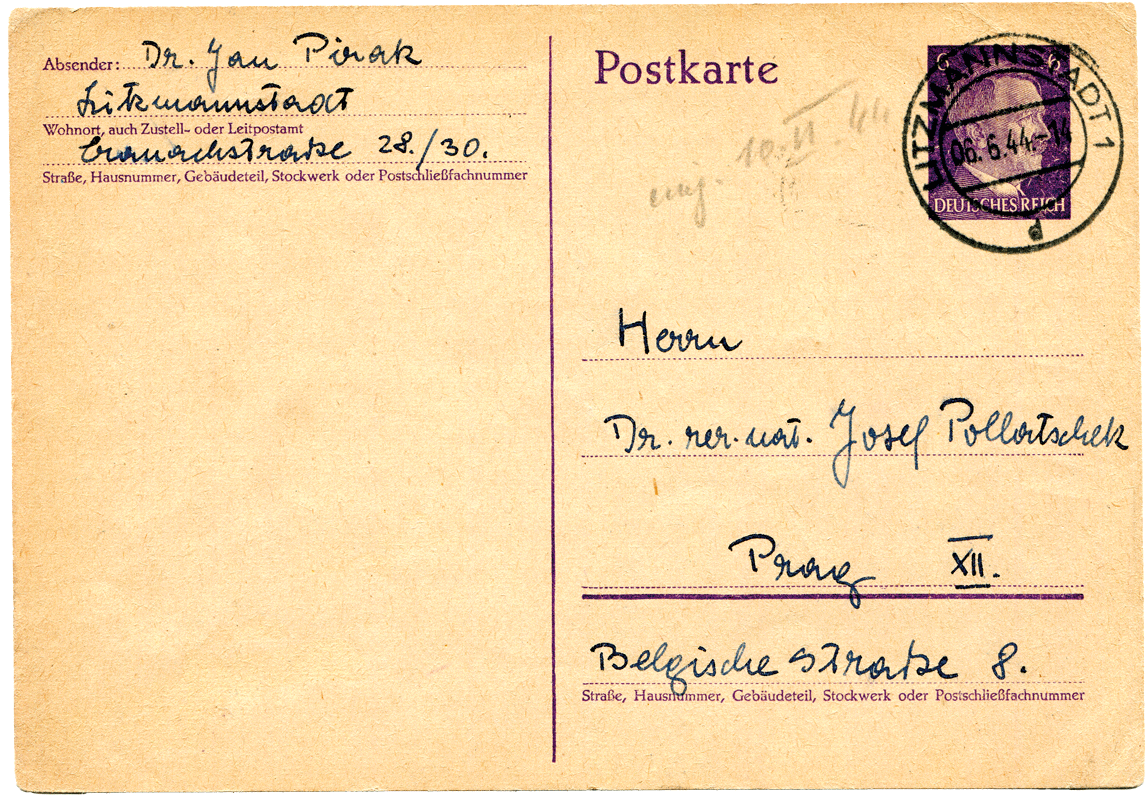

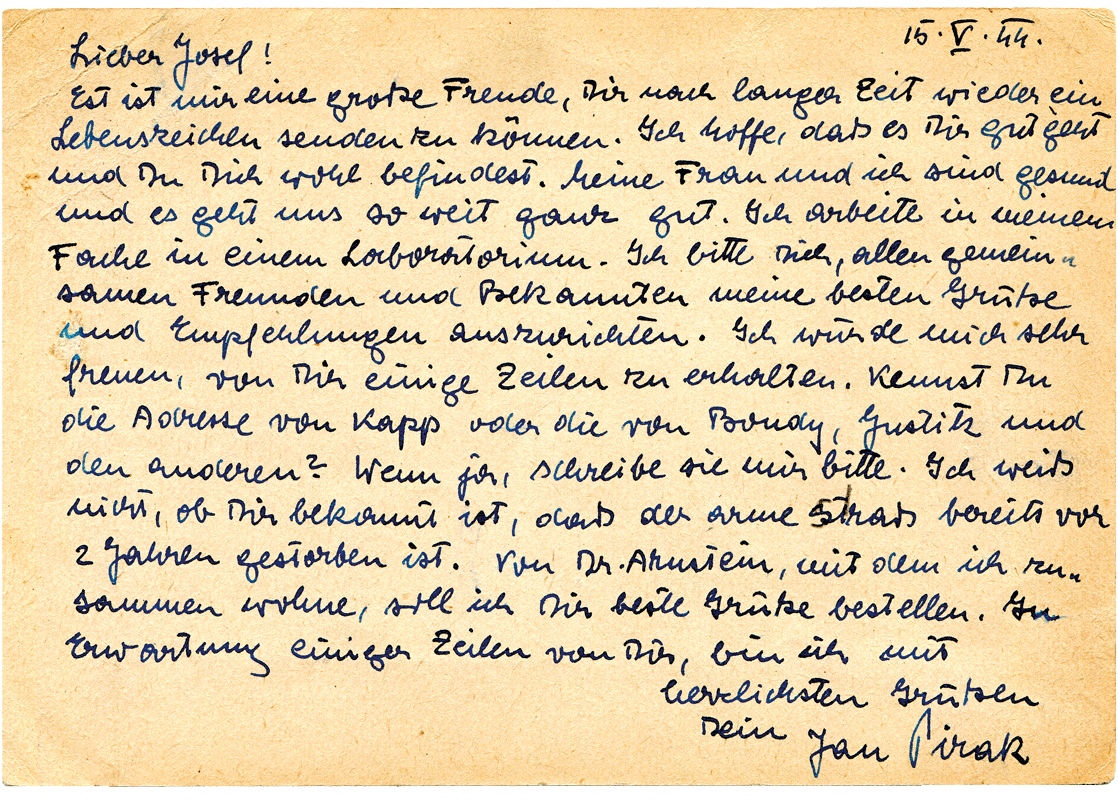

Ban on mail lifted

The suspension of the correspondence ban, which

had been in place for two and a half years, reverberated widely among people and was commented

on a regular basis in the Chronicle,

written in the ghetto. Most emotional was this fact among Jews

deported to Lodz in the fall of 1941 from the Reich and the

Protectorate, especially the large group coming from Prague. For Lodz

Jews, the lifting of the ban on correspondence was linked to the

realization that there was a shortage of people to whom one could

write

Chronicle of the Łódź Ghetto, May 9, 1944.

“ Ban on mail lifted

The major

development today is the news that the ban on mail has been lifted.

The spokesman for the post office in the 6th Police Station arrived

in the ghetto with this news in the predawn hours and immediately

everyone knew about it. The ghetto would be able to write and receive

mail again. It has been almost two and a half years since the ghetto

was completely isolated from the outside world, and now the residents

of this imprisoned city will be able to make contact with their

relatives again. First it was said that it would be possible to write

anything, in letters and on cards. That it would be possible to

receive packages and look for relatives. The ghetto is overjoyed. Of

course, there are many who receive this news with mixed feelings. The

only ones who have had relatively constant contact with relatives

outside the ghetto are the 250-300 or so resettlers from Prague who

still receive food parcels from the Protectorate of Bohemia and

Moravia, primarily from Prague. Living there now are probably Jews

living in Aryan families who were lucky enough to be allowed to

remain in their own homeland. They remember their relatives and send

bona fide parcels. But to whom should others write? To their

relatives who at one time fled Lodz? Who knows if they are alive,

where they are? To fathers, mothers and children displaced from the

ghetto? Who knows if they are still alive, where are they? The people

resettled here from the former Reich and Vienna also have little hope

of making contact with their relatives, because they too have no idea

of their whereabouts. Only if the Jews in the Reich, the Protectorate

of Bohemia and Moravia and the General Government learn that the

postal blockade has been suspended and hear from them themselves

could contacts be established again. Many, unfortunately too many,

are afraid of these contacts, for they can learn only bad things.

It

is only in the evening, after 5 o'clock, that the storming of the

Post Office Department at 4 Church Square begins. Mainly these are

the displaced, who now hope to make contact with relatives and

receive packages. But the post office is still not working today.

Clear guidelines on what and where to write have not yet arrived. The

news that it will be possible to write to the former Reich, to

Bohemia and Moravia, to the General Government, to the occupied

territories and even to neutral foreign countries seems at first

glance too far-fetched and optimistic.

In any case, the entire

ghetto is clearly excited, and groups can be seen everywhere

discussing the issue. A mass assault in the coming days is already

ruled out for the reason that the Postal Department temporarily does

not have. postcards and stamps at all. At the moment it is completely

impossible to assume that letters will be allowed, because if stamps

were not allowed to be affixed even to postcards, a closed letter is

not an option at all. We won't know more until tomorrow. “

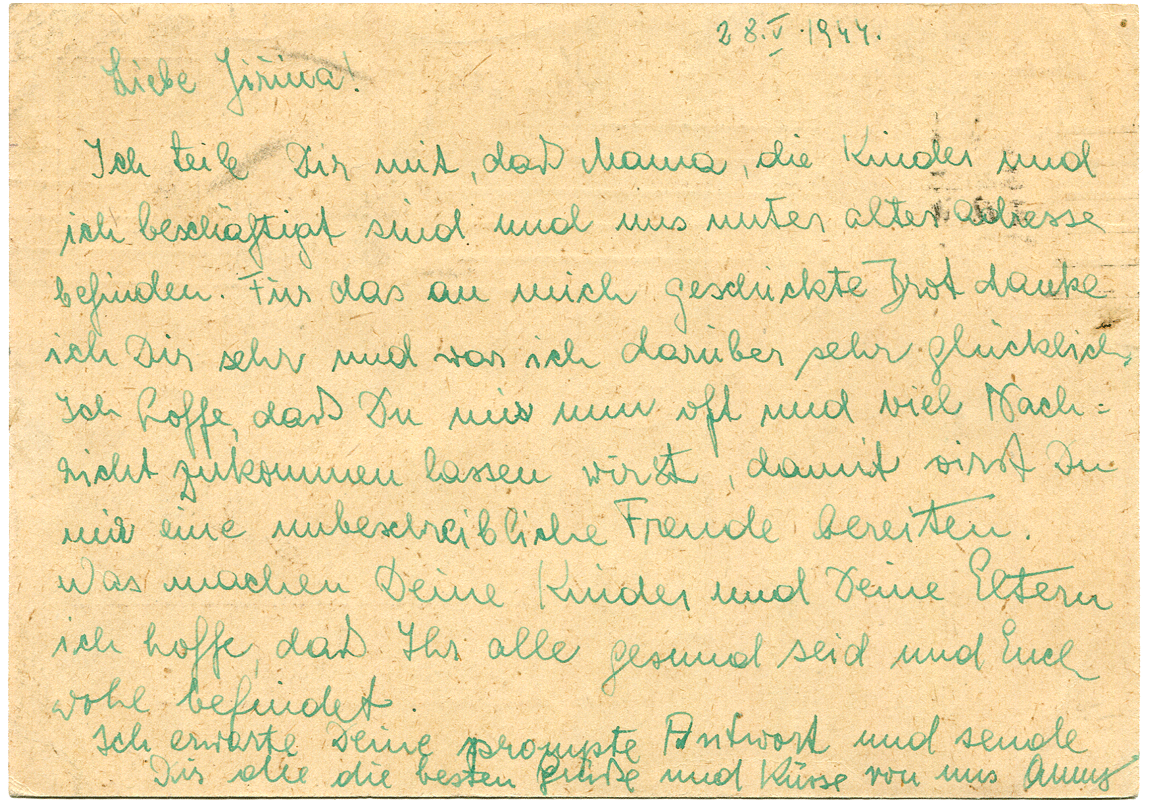

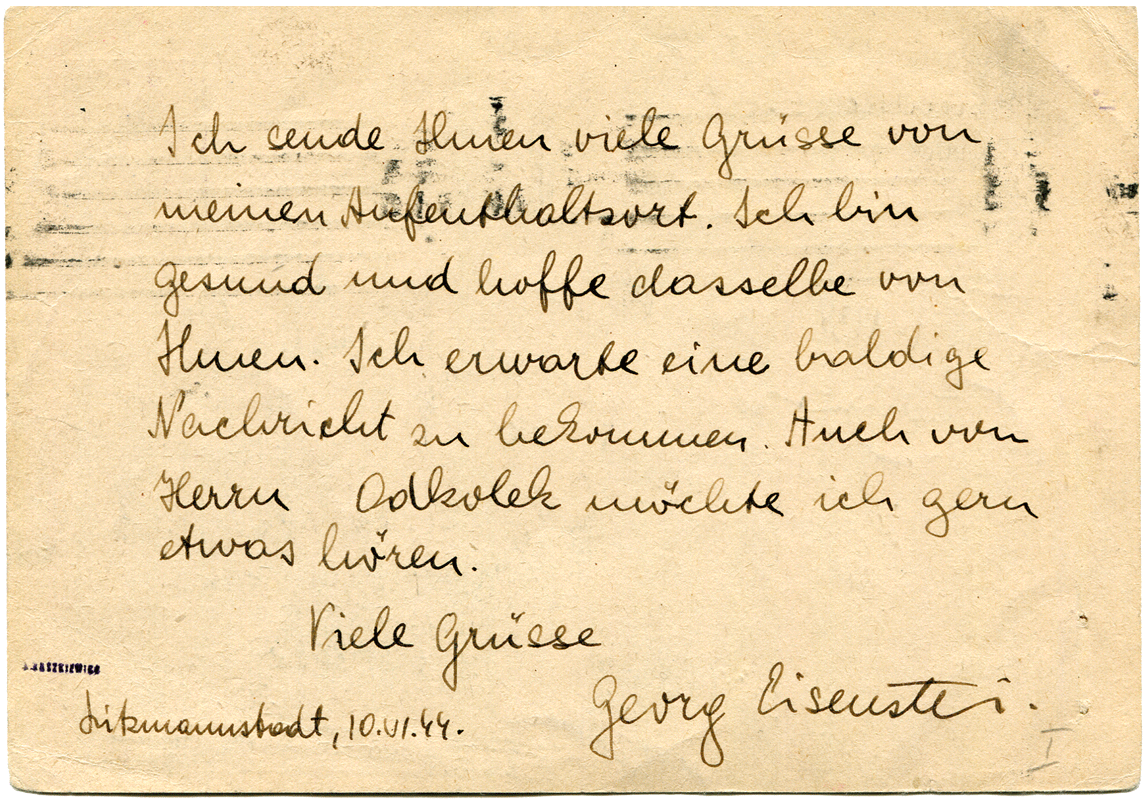

Chronicle of the Łódź Ghetto, May 10, 1944.

“ Ban on mail lifted

The

situation has since clarified. Only postcards are allowed, namely to

the former Reich, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the

General Government. It is only permitted to write to relatives with

brief information about the family. It is not permitted to ask for

food to be sent, but it is permitted to acknowledge receipt of bread.

(It is not allowed to confirm receipt of parcels.) The Postal

Department will only issue a sufficient number of postcards in 2-3

days. The cards sent in the meantime at the post office window will

be collected and inspected by the Jewish censors. At the Postal

Department, we learn that the material will later be subjected to

German censorship as well. Even though this restriction certainly

diminishes hopes a bit, the joy in the ghetto is still great,

however. The feeling that, after all, it will again be possible to

make contact with people outside the ghetto means, after all, that

the previous mental burden has been lightened. “